The blue flag

or, The Covenanters who contended for "Christ's crown and covenant"

by Robert Pollok Kerr.

Read or Free Download Online

or, The Covenanters who contended for "Christ's crown and covenant"

by Robert Pollok Kerr.

Read or Free Download Online

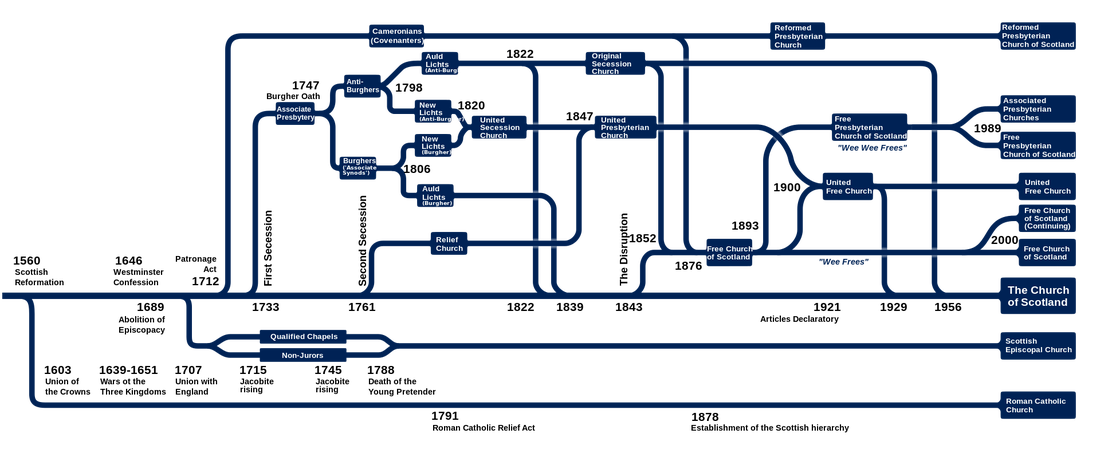

Church of Scotland Timeline

轉載自:From Wikimedia Commons

轉載自:From Wikimedia Commons

|

北美改革宗長老會歷史

唐興 譯

北美改革宗長老會(Reformed Presbyterian Church of North America, 簡稱:RPCNA)是基督教中一個很小的長老會宗派,分佈於美國、加拿大、中國和日本的一小部分。其信仰在更正教會中是屬於改革宗家庭保守的一個支翼。處於神所啟示和無誤的聖經之下,此教會持守幾個「從屬於聖經的信仰標準」:西敏斯特信仰告白以及西敏斯特大、小要理問答,並與教會的見證、教會治理規範、教會紀律規則和敬拜規範,一同被視為是教會的憲章。所有領聖餐的會員都「相信舊約和新約聖經是神的話,是信仰和生命唯一無誤的準則」,並且按照教會首要的誓言要求下成為會員。

RPCNA 有一個長遠的歷史,從美國殖民時期開始,她就是一個獨立的宗派。此外,在蘇格蘭(此宗派的發源地),從17世紀開始改革宗長老會就已經是一個獨立的宗派。PRCNA 現今宣告她與原始的蘇格蘭長老會的身分相同,並且是出自於16世紀的更正教宗教改革運動的。(註1) 其名字表示RPCNA是藉由「長老系統」來管理的(此宗派認為這是上帝所指示唯一的教會管理方式):每一個單獨的教會(congregation)都受到兩個或多個長老的治理。與多數的長老會宗派一樣,RPCNA 分為幾個不同的區會(presbyteries),但是與一些較小的長老會宗派不同之處在於: 此宗派最高的治理團體是單一的總會(synod), 而非大會(general assembly)。每一個教會可以差派一個長老代表(大教會可派兩個代表)參與其區會會議,以及年度性的總會會議。每一個牧師,無論服事教會與否,都自動的成為參與其所屬的區會和總會的代表。 以下的用詞是出自於RPCNA教會憲章中的教會治理規範: 受過洗禮的會員(baptised member):是那些已經受過洗但尚未表白基督教信仰的會員(通常多是領聖餐會員們的兒女)。受過洗禮的會員不能領受主餐或是在教會會議中參與投票。 領聖餐的會員 (communicant member):是指表明基督教信仰和持守宗派規範的會員。領聖餐可以領受主餐和在教會事務會議中投票。 長老(elder):是指被選舉出來和被按立來領導教會者。長老包括治理長老(平信徒)和教導長老(神職人員),他們在身分上被視為平等,但具有不同的角色。在一般的情況下,每一位長老都是其教會堂會(session)的成員,如同每一位現役的牧師。然而,目前非現役的牧師可只能作為其教會的治理長老。每個教會都必須至少有兩位長老,才能合法的成立。 區會(presbytery):是指在一個特定的地域範圍內的眾教會所組成的群體,受到該地域範圍內的牧師們的治理,包括那些教會中的一位或多位的治理長老們。 堂會(session):是指每個教會中的治理委員會(governing board),由該教會中的長老們和牧師們所組成。 總會(synod): 是指在區會之上的治理團體,由所有的牧師們和一位或多位屬於此宗派的各教會的長老們所組成。 起源 Origins 從歷史上來說,改革宗長老會也就是指那些「立盟約者」(covenanters),因為他們與始於16世紀蘇格蘭的民眾立約運動認同。這個運動是為了回應當時的國王違反先前與自由大會和國會(free assemblies and parliament)之間的協議(盟約),企圖要改變教會的敬拜形式和治理方式,許多牧師們為了堅定持守那些先前的協議,於1638 年2月在愛丁堡的葛萊非教堂(Greyfrias Kirk)共同簽署了所謂的“國家盟約”(National Covenant)。「藍旗」(blue banner)就是從這裏開始的,它宣告:「為基督的榮冠與聖約」(For Christ's Crown & Covenant),因為立盟約者們有鑑於國王要改變教會,就是企圖要篡奪耶穌基督的元首地位。1643年8月,立盟約者們與英國國會共同簽署了一個政治協議,稱為「莊嚴結盟與立約」(the Solemn League and Covenant)。在此盟約之下,簽署者們同意在英國和愛爾蘭成立長老教會(Presbyterianism)作為國家教會。「立盟約者」們同意支持英國國會一同在英國內戰中反對英王查理一世。「莊嚴結盟與立約」堅持基督「榮冠權」(crown rights) 的權限是高於教會和政府的,並且教會具有免於政府強制干涉的自由。當奧利弗·克倫威爾(Oliver Cromwell)在英國把權力交到獨立者的手中時,也就標誌著國會所應許的改革已經結束了。 當1660年帝制恢復的時候,一些長老教會人士期盼新立約的國王,查理二世能在1650和1651年宣誓進入盟約。然而,查理二世決定他不聽從任何有關立約的說詞。當大多數的人們參與已經建立好的教會時,立約者強烈的表達異議,並在郊外地區舉行非法的崇拜。他們在接踵而至的巨大逼迫中飽受困苦,其中最有名的就是在查爾斯二世和詹姆士七世在位時所執行的所謂的「殺戮時刻」(Killing Times)。 1691年,長老教會恢復成為蘇格蘭被認可的教會。因為就「莊嚴結盟與立約」而言政府並沒有承認基督的權柄,所以一群異議人士就拒絕接受此國家性的安排(所謂的「改革調停」),其理由是此決議是強迫加諸於教會的,沒有固守國家先前的盟約協議。這些造就了一些社會團體,最後形成了蘇格蘭的改革宗長老教會。同時,當查理二世宣布「蘇格蘭立約者」為非法時,爆發了對教會的逼迫,在1660年到1690年之間,成千上萬的「蘇格蘭立約者」逃到阿爾斯特(Ulster)。最後,這些立約者在愛爾蘭成立了改革宗長老教會。 改革結束之後,剩餘的一些「立約者」牧師們則於1690年加入了英國國教(the Established Church),使得「聯合會」(the United Socities)沒有任何牧師長達十六年之久。1706年,英國國教的一位牧師改變心意信服了「立約者」的原則,加入了他們的行列。然而,直到1743年才有另外一位牧師加入。長老會制度就立刻成形了,使愛爾蘭和蘇格蘭教會的牧師按立得以進行。在二十年中愛爾蘭的教會被正式地組織起來。 然而,政治戰爭,像1798年的愛爾蘭暴動(Irish Rebellion),開始困擾著愛爾蘭的「立約者」。雖然沒有參與任何一方,他們拒絕立誓效忠英國政府,使得某些政府官員認為他們是反動份子,把他們看為是「愛爾蘭聯合會」(Society of the United Irishmen)(Glasgow 77-78)。結果許多愛爾蘭的「立約者」就逃至美國尋找自由。而到美國追尋新生活的蘇格蘭「立約者」就與這些殖民人士聯合起來,成為美國改革宗長老會的創立成員。 後續的歷史 Subsequent history 1738年在賓州蘭卡斯特郡(Lancaster County, Pennsylvania)的中奧克多拉(Middle Octorara)成立了首間改革宗長老會,但由四位愛爾蘭移民者和蘇格蘭改革宗長老會牧師們所組成的「區會」一直到1774年才成立。這時候,改革宗長老會多集中在賓州(Pennsylvania)東部和南卡(South Carolina)北部,但在麻州(Massachusetts,)康州(Connecticut,)紐約州(New York,)賓州西部,北卡(North Carolina,)和喬州(Georgia)也有少數的改革宗長老會。美國革命時期,多數的改革宗長老會人士都參與了獨立戰爭-1780年南卡的一位牧師甚至被以暴動之名遭逮捕到康沃利斯(Lord Cornwallis)將軍面前。 1691年「改革調停」(Revolution Settlement)時,改革宗長老會首要的「特殊原則」(distinctive principles)就是要處理從英國政府而來的異議。在美國憲法被通過之後,本宗派認為此文獻是不道德的,並且參與這樣的政府也同樣是不道德的,因為憲法不承認基督是列國之王。因此,許多公民權,如投票和陪審義務,都被免除了,而且教會法庭訓誡那些參與這些公民權的會員。當美國沒有人持守那些原則,並且順服有時會造成困難(譬如:效忠誓言被禁止,在國外出生的改革宗長老會人士被禁止成為公民,禁止改革宗長老會人士受益於「公地放領法」(Homestead Acts))的時候,許多改革宗長老會人士就開始與宗派的正式立場不一致了。從1774年起,此宗派就開始經歷四個主要的分裂,其中三次分裂是因為那些會員們認為宗派的立場過於嚴厲。

即使存在這些異議,此宗派仍然持守著其教義沒有任何改變。所持守的原則就是,盟約必須繼續的被更新和起誓,RPCNA 承襲了「1871年之盟約」做為那年教會的新盟約。一些會員視此盟約的某些方面與歷史改革宗長老會的立場相距甚遠,造成一些人離開加入改革宗長老區會(Reformed Presbytery)。 19世紀期間最持久的改變就是對社會改革運動的參與。此宗派所支持的一件事就是「廢除奴隸制度」,從1800年開始,就正式地禁止會員擁有奴隸以及參與奴隸交易。大多數的會員都熱烈地支持,宗派採取強烈的立場反對邦聯(Confederacy)並且一心地支持「美國內戰」的北方,改革宗長老會參戰反對「擁有奴隸者的反動」。廢除奴隸制度成為南卡羅南納州和田納西州諸教會衰微的主要原因:那些地方多數的會員,發現在擁有奴隸的社會裏,做為反對奴隸制度者是困難重重,因此而遷移到南方的俄亥俄州,印第安納州,和伊利諾州;到內戰開始的時候,南卡州和田納西州的老教會都已人去樓空了。在擁有奴隸的區域中僅存的一些教會,分佈於巴爾的摩(Baltimore),馬里蘭(Maryland),和維吉尼亞州的羅尼點(現在的西維吉尼亞州),靠近威嶺市(Wheeling)。另外一個社會實踐主義所專注的地方就是酒和煙草(alcohol and tobacco)。當醉酒一直是被禁止的事,1841年時候的會員是被禁止從事賣酒的生意的,到了1880年代,教會職事和一般會員都禁止飲酒。到1886年,煙草也同樣受強烈譴責的,任何飲用酒或煙草者都禁止被按立。結果,此宗派幾十年以來明白的支持美國憲法第十八條修正案,和其他的禁止行動。 從愛爾蘭和蘇格蘭移民來美國的改革宗長老會,維持了宗派的成長。一些特別是在東部海岸的教會得以快速成長;超過九十人的會員在三年之內加入了巴爾的摩、馬里蘭的教會。當會員向美西遷移之時也成立了許多教會。1840年時,東部海岸城市有四間教會,密西西比河以西則無任何教會,最西邊的教會位於伊利諾州西南方。1865年,東部海岸城市有九間教會,密西西比以西有八間教會,最遠到愛荷華州西南方。1890年,西部海岸城市有十二件教會,密西西比河以西有三十五間教會,最遠到華盛頓州的西雅圖市。也形成了更多的區會:1840年5個區會;1850年5個區會;1860年6個區會;1870年8個區會;1880年10個區會;1890年11個區會。 19世紀中葉的幾十年中,改革宗長老會經歷了廣布的成長。多數東部的教會組織在都市裡,許多其他的教會則都是郊區教會。然而越往西部,多數的教會都在郊區。這是因為多數改革者長老會的移民者的生活型態。一般而言,大群的移民者會聚集在適合耕種的地區,他們就組織成一個教會:堪薩斯州的北衫教會(North Cedar congregation in Denison, Kansas)在1870年時尚未存在,但是到了1872年時卻有84位會員。其他的成長有其他的緣由。雖然美國的會員從1789年就受到美國教會的治理,蘇格蘭和愛爾蘭的總會仍然繼續向加拿大宣教。經過多年,一些蘇格蘭總會的教會也加入了北美總會,藉著愛爾蘭總會的祝福,一整個的區會(新不倫瑞克省 New Brunswick 和新斯科舍省Nova Scotia)在1879年轉入北美總會。多年以來,除了這些教會以外,沒有整個教會加入RPCNA的情形,即使1969年餘留的聯合長老會與RPCNA合併(此刻聯合長老教會只剩四間)。 經過六十年持續的成長之後,1891年的宗派分裂導致了宗派全面性的衰退。即使1200位會員的離開,仍然留下一萬個領聖餐的會員,但是幾近持續的流失導致到1980只年剩3,804個領聖餐的會員。在這段時間內,東部大都市中的大教會漸漸凋零:1891年時在麻塞諸塞州的波士頓市還有兩家教會,紐約市有五家,賓夕法尼亞州的費城有三家,在巴爾的摩有一家教會;到了1980年,波士頓、紐約和費城總共只剩四家教會。在美國西部的殖民和成長繼續了一段時間,新的長老會在科羅拉多州,以及太平洋海岸和加拿大草原省(Prairie Provinces of Canada)被組織成立起來。然而,郊區的教會也衰落了,從1891年的83間教會到1980年的25間教會。區會也變得亂序和合併了,1980年四個區會(費城、紐約、佛蒙特、新斯科舍省)被合併成為紐約區會(後來重新命名為大西洋),紐約市的五間教會共1,075位會員縮減到一間僅有四十人的教會。雖然大量人數的流失是因為個人的離開加入其他教會,但是有些流失牽涉到多人一次性的離去。例如,1912年100多位會員離開第一波士頓教會,是因為他們的牧師離開了宗派。1906年和1919年,佛蒙特教會和第二紐博格教會分別離開了宗派。1910年代中葉,就連新教會的建立都是不尋常的事,1920和1930年代僅各有三間教會被建立,1937到1950年之間,沒有建立任何教會。 信仰與實踐 Beliefs and Practices 至17世紀以來,改革宗長老會就一直持守著《西敏斯特信仰告白》和《西敏斯特要理問答》。沒有像其他的北美長老會一樣,採用了《信仰告白》的修訂版本,RPCNA維持了原始的文字,但是在其官方文獻中說明了異議,與《信仰告白》並列印出。今天,除了限定《信仰告白》稱教皇為敵基督之外,僅有三個小地方受到RPCNA的反對。堅持這些教義的結果,使得RPCNA在教義上更接近其他改革宗教會。 從歷史上來說,改革宗長老會的「特殊原則」(distinctive principles)是政治性的:它們持守一種「立約者」所延續下來的責任,在國家以及莊嚴結盟方面都是如此,所有曾經起誓者和所有他們的後代也都如此持守,認為反對這些文獻的政府,會使得這些政府成為不道德的,甚至不配順服。這些導致他們在「榮耀革命」(Glorious Revolution)之後反對蘇格蘭政府,以及愛爾蘭和英國政府(這些政府起先承認盟約但後來又放棄了)。此外,在「莊嚴結盟」之時,美國是有責任要持守這些盟約的。因為,美國憲法沒有任何條文提到基督或諸盟約,改革宗長老會者就拒絕投票、擔任政府公職、作法院陪審,或向美國聯邦政府或任何底層政府起誓效忠。加拿大的會員們也都同樣地不參與這些活動。那些參與這些政治活動的會員,通常會遭到教會堂會的紀律管教。雖然這些原則被堅定地持守了幾十年,從1960年代開始,宗派正式的立場產生了改變;到了1969年,官方正式的立場允許會員參與投票和競選公職。然而一些會員們仍然繼續歷史的異議立場,但是大多數的會員與保守的基督教宗派一樣都參與政治活動。改革宗長老會者包里安(Bob Lyon)於2001年到2005年從政於堪薩斯州為州議員。 另外一個RPCNA長期持守與其他教會不同的信仰就是,禁止「旁聽左道」(occasional hearing) (參與其他宗派牧師的敬拜和講道)。雖然現在允許此慣例,但長久以來是被禁止的。例如,賓州東部某教會的紀錄顯示:1821年,兩位女仕曾因為參加一個循道會(Methodist)的周間營會,而被「嚴厲地訓誡」。禁止此事的原因是具有歷史立場的:作為蘇格蘭教會的成員,是改革宗長老會所繼續承認的,是在全英國被建立的國家教會。改革宗教會認為這種地位從來沒有被官方正式的在法律上廢除,所以視其他教會不具法律上存在的權利。因此,參與其他教會的敬拜等於就是參加非法組織。 改革宗長老會一直都持守「敬拜的一般規範原則」(the regulative principle of worship)並且把此原則實踐出來:在敬拜的時候用《詩篇》無伴奏合唱(acappella)。雖然這種實踐在過去的幾世紀中並非不尋常,但多年以來許多其他的宗派都已經允許詩歌和樂器配樂了。結果,RPCNA的敬拜型態在今天就顯得頗為特別。在官方對政治活動的立場改變了之後,敬拜的型態就成了RPCNA主要的特徵。(註1) 雖然喝酒是所有會員幾十年以來被禁止的,近年來一般會員和被按立的職分已經被允許使用。《RPCNA 見證》第26章說明了戒用酒精飲料仍然是基督徒合宜的選擇 (參考:基督教與喝酒)。 與許多其他的保守宗派一樣,RPCNA 對聖經的解釋是要求所有的長老都為男性。然而,與一些關係最親的宗派不同之處,在於RPCNA 的執事們可以是男性或女性;從1888年開始就允許女執事(一直到2002年企圖限制男執事的提案都沒有成功)。在1930年代,總會投票表決女長老的按立,但是無法得到足夠堂會數目的批准,這是教會治理章程所有的改變都需要經過的一個程序。 主餐的聖禮,或聖餐,是為到教會領受聖禮的所有領聖餐會員所提供的。直到最近幾十年,唯有改革宗長老會者才被准許參與聖禮,但是最近幾十年,這項權益也延伸納入了承認聖經的其他宗派。然而,RPCNA 要求其他宗派會員參與領聖餐之前必須個別地接受堂會的諮詢,這也是RPCNA另外一項不同於其他改革宗宗派的特殊的實施慣例。 北美改革宗長老會也是「北美長老會區會和改革宗理事會」(North American Presbyterian and Reformed Council, NAPARC)的成員。這是一個認信長老會和洲際改革宗教會的組織,成員也包括了正統長老會,美國長老會,北美聯合改革宗教會,美國改革宗教會和聯合改革宗長老會,以及一些其他小的改革宗和長老會宗派。 譯者註:

1. 請參考:「蘇格蘭教會歷史」和「蘇格蘭基督教歷史」 2. 關於「獨頌詩篇」 EP(Exclusive Psalmody)在改革宗大家庭中持不同意見之聖經和神學論述,請參考:獨頌詩篇-鼓勵和保存合乎聖經的敬拜(Exclusive Psalmody-For the Encouragement and Preservation of Biblical Worship )。 約翰諾克斯和蘇格蘭的立盟約者

John Knox and The Scottish Covenanters |

History of the

Reformed Presbyterian Church of North America 轉載自:Wikipedia

The Reformed Presbyterian Church of North America (RPCNA), a Christian church, is a smallPresbyterian denomination with churches throughout the United States, in Canada, and in a small part of Japan. Its beliefs place it in the conservative wing of the Reformed family of Protestant churches. Below the Bible—which is held as divinely inspired and without error—the church is committed to several "subordinate standards", together considered its constitution: the Westminster Confession of Faith and Larger and Shorter Catechisms, along with its Testimony, Directory for Church Government, Book of Discipline, and Directory for Worship. All communicant members "believe the Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments to be the Word of God, the only infallible rule for faith and life", according to the first of several vows required for such membership.

The RPCNA has a long history, having been a separate denomination in the United States since colonial days. Furthermore, in Scotland (where the denomination originated), Reformed Presbyterians have been a separate denomination since the late 17th century, and today the RPCNA claims identity with the original Presbyterian Church of Scotland that came out of the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century. As its name suggests, the RPCNA is governed through the Presbyterian system (which the denomination considers to be the only divinely-appointed method of church government), with each individual congregation being governed by two or more elders. As with most Presbyterian denominations, the RPCNA is divided into several presbyteries, but unlike several other smaller Presbyterian denominations, the supreme governing body is a single synod, not a general assembly. Each congregation may send one elder delegate (two for larger congregations) to its presbytery meeting, as well as to the annual Synod meeting. Each minister, whether serving as the pastor of a congregation or not, is automatically a delegate to his presbytery and to Synod. The following terminology is derived from the Directory for Church Government in the RPCNA's church constitution: · Baptized member: a member, almost always the child of communicant members, who has been baptized but has not yet professed Christian faith. Baptized members may not receive the Lord's Supper or vote in congregational business meetings. · Communicant member: a member who has professed Christian faith and adherence to denominational standards. Communicant members may receive the Lord's Supper and vote in congregational business meetings. · Elder: a man elected and ordained to lead a congregation. This includes both ruling elders (laymen) and teaching elders (clergy), which are considered equal in status but different in role. Under normal circumstances, each ruling elder is a member of his congregation's session, as is every active pastor. However, an ordained minister who is not currently active as a pastor may serve only as a ruling elder in his congregation. Each congregation must have at least two elders in order to be legitimately constituted · Presbytery: a group of several congregations in a specific area, governed by the ministers in that area along with one or more ruling elders from each of those several congregations. · Session: a governing board in each congregation, composed of the elders in that congregation and the congregation's pastor(s). · Synod: a governing body above the presbytery, composed of all ministers and one or more elders from each congregation in the denomination. Origins Reformed Presbyterians have also been referred to historically as Covenanters because of their identification with public covenanting in Scotland, beginning in the 16th century. In response to the King's attempts to change the style of worship and form of government in the churches that had previously been agreed upon (covenanted) by the free assemblies and parliament, a number of ministers affirmed their adherence to those previous agreements by becoming signatories to the "National Covenant" of February 1638 at Greyfriars Kirk, in Edinburgh. It is from this that the Blue Banner comes, proclaiming "For Christ's Crown & Covenant", as the Covenanters saw the King's attempt to alter the church as an attempt to claim its headship from Jesus Christ. In August, 1643, the Covenanters signed a political treaty with the English Parliamentarians, called the "Solemn League and Covenant". Under this covenant the signatories agreed to establish Presbyterianism as the national church in England and Ireland. In exchange, the "Covenanters" agreed to support the English Parliamentarians against Charles I of England in the English Civil War. The Solemn League and Covenant asserted the privileges of the "crown rights" of Jesus as King over both Church and State, and the Church's right to freedom from coercive State interference. Oliver Cromwell put the independents in power in England, signaling the end of the reforms promised by Parliament. When the monarchy was restored in 1660, some Presbyterians were hopeful in the new covenanted king, as Charles II had sworn to the covenants in Scotland in 1650 and 1651. Charles II, however, determined that he would have none of this talk of covenants. While the majority of the population participated in the established church, the Covenanters dissented strongly, instead holding illegal worship services in the countryside. They suffered greatly in the persecutions that followed, the worst of which is known as the Killing Times, administered against them during the reigns of Charles II and James VII. In 1691, Presbyterianism was restored to the Established Church in Scotland. Because there was no acknowledgement of the sovereignty of Christ in terms of the Solemn League and Covenant, however, a party of dissenters refused to enter into this national arrangement (the “Revolution Settlement”), on the grounds that it was forced upon the Church and did not adhere to the nation's previous covenanted settlement. These formed into societies which eventually formed the Reformed Presbyterian Church in Scotland. Meanwhile, when persecution broke out after Charles II had declared the Scottish Covenants illegal, tens of thousands of Scottish Covenanters had fled to Ulster, between 1660 and 1690. These Covenanters eventually formed the Reformed Presbyterian Church in Ireland. After the Revolution Settlement, all of the few remaining Covenanter ministers joined the Established Church in 1690, leaving the "United Societies" without any ministers for sixteen years. In 1706, one minister of the Established Church became convinced of Covenanter principles and joined them, but it was not until 1743 that another minister joined them. Immediately a presbytery was formed, allowing the ordination of other ministers for Irish and Scottish churches. The Church in Ireland was formally organized within twenty years. However, political fighting, such as the Irish Rebellion of 1798, began to cause problems for Irish Covenanters. Although they did not join either side, their refusal to take oaths of loyalty to the British government led some government officials to consider them rebels, similar to the Society of the United Irishmen (Glasgow 77-78). As a result, many Irish Covenanters fled to find freedom in America. Joined by Scottish Covenanters seeking a new life in America, these settlers were the founding members of the Reformed Presbyterian Church in America. Subsequent history The first Reformed Presbyterian congregation in North America was organized in Middle Octorara (Lancaster County, Pennsylvania) in 1738, but the first presbytery, organized by four immigrant Irish and Scottish Reformed Presbyterian ministers, was not formed until 1774. At this time, Reformed Presbyterians were mostly concentrated in eastern Pennsylvania and northern South Carolina, but small groups of Reformed Presbyterians existed in Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, westernPennsylvania, North Carolina, and Georgia. During the American Revolution, most Reformed Presbyterians fought for independence—the one minister that served in South Carolina was even arrested for insurrection and brought before Lord Cornwallis in 1780. From the time of the Revolution Settlement in 1691, the foremost of Reformed Presbyterian "distinctive principles" was the practice of political dissent from the British government. After the adoption of the United States Constitution, the denomination held the document (and therefore all governments beneath it) to be immoral, and participation in such a government to be likewise immoral, because the Constitution contained no recognition of Christ as the King of Nations. Therefore, many civic rights, such as voting and jury service, were waived, and church courts disciplined members who exercised such civic rights. As few Americans held such principles, and as obedience sometimes caused difficulty (for example, oaths of allegiance were prohibited, preventing foreign-born Reformed Presbyterians from becoming citizens, and preventing Reformed Presbyterians to make use of the Homestead Act), many Reformed Presbyterians began to differ with the denomination's official position. Since 1774, the denomination has undergone four major schisms, three of them due to members who considered the denomination's position to be too strict. · In 1782, almost all of the church merged with the Associate Presbyterian Church (the Seceders) to form the Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church, holding that the new situation of independence removed the reasons for political dissent. The few remaining members who refused to join the merger, including just two congregations, were reorganized into a presbytery in 1798. · In 1833, the church split down the middle, forming the New Light and Old Light RP Synods. The New Lights, who formed the Reformed Presbyterian Church, General Synod and exercised political rights, grew for some years but suffered splits and went into decline, eventually merging in 1965 with theEvangelical Presbyterian Church (formerly the Bible Presbyterian Church-Columbus Synod) to form the Reformed Presbyterian Church, Evangelical Synod, which in 1982 merged with the Presbyterian Church in America. · A third split, in 1840, resulted in two ministers and a few elders leaving to form the Reformed Presbytery (nicknamed the Steelites, after David Steele, their most prominent leader), which continues today. Unlike with the other splits, this was occasioned by the departed ministers and members holding that the denomination itself had fallen away from its covenants and "historical attainments" by allowing "occasional hearing," political activity, and membership in "voluntary associations". · The main body of the RPCNA suffered another split, the "East End Split", in 1891, again on the matter of political activity and office-holding. Statistics reveal that denominational membership suffered a net loss of 11% in 1891, most of whom joined the United Presbyterian Church. Despite such disagreements, the denomination held to its doctrines with few changes. Holding to the principle that covenants should continue to be updated and sworn, the RPCNA adopted the "Covenant of 1871" as their new church covenant in that year. Some members saw certain aspects of this covenant as major departures from historic Reformed Presbyterian positions, causing some to leave and join the Reformed Presbytery. Perhaps the most enduring change during the 19th century involved participation in social reform movements. One cause favored by the denomination was the abolition of slavery, beginning officially in 1800, when members were prohibited from slave owning and from the slave trade. Enthusiastically supported by most members, the denomination took a strong stance against the Confederacy and faithfully supported the North in the Civil War, as Reformed Presbyterians enlisted to fight against the "slaveholders' rebellion." Abolition was a major factor in the decline of the denomination's South Carolina and Tennessee congregations: most members there, finding it hard to be abolitionists in slave-owning societies, moved to southern Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois; by the beginning of the Civil War, all of the old congregations in South Carolina and Tennessee were gone. The only congregations remaining in slave-holding territory were in Baltimore, Maryland, and in Roney's Point, Virginia (nowWest Virginia), near Wheeling. Another area of social activism focused on alcohol and tobacco. While drunkenness had always been prohibited, members were prohibited from the alcohol business in 1841, and by the 1880s, both church officers and ordinary members were prohibited from alcohol use. By 1886, tobacco use was strongly condemned as well, with ordination being prohibited to anyone who used it. As a result, the denomination explicitly supported the Eighteenth Amendment and otherprohibition efforts for many decades. Immigration from Reformed Presbyterian churches in Ireland and Scotland provided sustained growth for the denomination. Some congregations, especially those on the East Coast, saw rapid growth; over ninety members, many of them immigrants, joined the Baltimore, Maryland, congregation in a single three-year period. Meanwhile, members moved west and many congregations were organized. In 1840, there were four East Coast city congregations and zero congregations west of the Mississippi River, the farthest west congregation being in southwestern Illinois. In 1865, there were nine East Coast city congregations and eight congregations west of the Mississippi, as far west as southwestern Iowa. In 1890, there were twelve East Coast city congregations and thirty-five congregations west of the Mississippi, as far west as Seattle, Washington. More presbyteries were organized as well: in 1840, there were 5; in 1850, 5; in 1860, 6; in 1870, 8; in 1880, 10; in 1890, 11. During the middle decades of the 19th century, the denomination experienced widespread growth. Many congregations in the East were organized in cities, while many others were countryside congregations. Farther west, however, most congregations were founded in the countryside. This is due in large part to the way of life of many Reformed Presbyterian settlers. Typically, a large group of settlers would gather and move to an area favorable for farming, where a congregation would soon be organized for them. Some congregations saw extremely fast growth in this way: the North Cedar (Denison, Kansas) congregation did not exist in 1870 but had eighty-four members in 1872. Other growth came from different sources. Although American congregations had been governed by an American church since 1798, the Scottish and Irish synods continued to operate missions in Canada. Over the years, several Scottish-synod congregations joined the North American synod, and with the blessing of the Irish synod, an entire presbytery ("New Brunswick and Nova Scotia") transferred in 1879. Few complete congregations have joined the RPCNA over the years, other than these, although the denomination has seen one merger: in 1969, the RPCNA merged with the remnants of the Associate Presbyterian Church, which by this point consisted of just four churches. After sixty years of nearly constant growth, the denominational split in 1891 led to a denomination-wide downturn. Although the departure of twelve hundred members in the split still left over ten thousand communicant members, nearly constant loss led to a total of just 3,804 communicant members by 1980. During this time, the large congregations in the big cities of the East gradually withered: while in 1891, there were two congregations in Boston, Massachusetts, five in New York City, three in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and one in Baltimore, in 1980 there were only four in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia combined. Settlement and growth in the western United States continued for a time, with new presbyteries being organized in Colorado, the Pacific Coast, and the Prairie Provinces of Canada. However, the countryside congregations also dwindled, from eighty-three in 1891 to twenty-five in 1980. Presbyteries, too, were disorganized and combined, with only seven presbyteries remaining in 1980. Perhaps the most drastic examples of both congregational and presbyterial decline involve New York: by 1980, four presbyteries (Philadelphia, New York, Vermont, and New Brunswick and Nova Scotia) had been combined into the New York Presbytery (since renamed Atlantic), while five New York City congregations with 1,075 communicant members had been reduced to one congregation of only about forty people. Although large numbers of losses were due to individuals leaving for other churches, some departures involved many people at once. For example, over 100 communicant members left First Boston congregation when their pastor left the denomination in 1912, while Craftsbury, Vermont and Second Newburg (New York) congregations left the denomination as entire congregations, in 1906 and 1919 respectively. After the mid-1910s, even the founding of new congregations was uncommon, with only three each in the 1920s and 1930s, and no new congregations at all between 1937 and 1950. Beliefs and Practices The Reformed Presbyterian Church has held to the Westminster Confession and Catechisms since the 17th century. Instead of adopting revised versions of the Confession, as has been done by other Presbyterian churches in North America, the RPCNA instead keeps the original text but states objections in its official Testimony, which is printed side-by-side with the Confession. Today, only three small portions of the original Confession are denied by the RPCNA, besides qualifying the Confession's naming of the Pope as Antichrist. As a result of adhering to these creeds, the RPCNA is doctrinally close to other Reformed denominations. Historically, the "distinctive principles" of Reformed Presbyterians were political: they held to a continuing obligation of the Covenants, both National and Solemn League, upon all who had sworn them and upon all their descendants, and the belief that governmental rejection of such documents caused the government to become immoral or even undeserving of obedience. This led them to reject the government of Scotland after the Glorious Revolution, as well as those of Ireland and England, which had also acknowledged but later dropped the Covenants. Furthermore, as the American colonies had been under English jurisdiction at the time of the Solemn League, the United States was held as responsible to uphold the Covenants. Since the Constitution contains no reference to Christ or to the Covenants, Reformed Presbyterians refused to vote, hold governmental office, serve on juries, or swear any oath of loyalty to the United States government or any lower government, and Canadian members similarly refrained from such activities. Members who did participate in the political process would typically be disciplined by their congregational session. Although these principles were held firmly for many decades, the official denominational position was changed, beginning in the 1960s; by 1969, the official position allowed members to vote and run for office. Some members yet continue the historic dissenting positions, but the majority of members participate like members of other conservative Christian denominations, and Reformed Presbyterian Bob Lyon served in the Kansas Senate from 2001 to 2005. Another long-held belief distinguishing the RPCNA from other churches was its prohibition of occasional hearing, the practice of attending worship services or preaching by ministers of other denominations. Although the practice is permitted today, it was long prohibited. For example, records from an eastern Pennsylvania congregation note that two women were "severely admonished" for attending a weekday Methodist camp-meeting in 1821 (Glasgow 273). The reasons for this prohibition were historical grounds: as the Church of Scotland, the continuation of which the Reformed Presbyterian Church considered itself, had been established as the state church throughout Great Britain. As the Reformed Presbyterian Church believed that had never officially been disestablished in a legal manner, it considered other churches to have no legal right to exist. Therefore, attending a worship service of any other church amounted to participation in an illegal organization. The denomination has always believed in the "Regulative Principle of Worship" and applied it to requirea cappella singing of the Psalms only in worship. While this practice was not unusual in past centuries, many other denominations have permitted hymns and instrumental music over the years. As a result, the RPCNA's manner of worship is quite distinctive today, and with the change in the official position on political action, the manner of worship is the chief distinction of the RPCNA today. Although alcohol use was prohibited for all members for many decades, in recent years both ordinary members and ordained officers have been permitted to use it. Chapter 26 of the RPCNA Testimony states that abstinence from alcohol is still a fitting choice for Christians. (Compare Christianity and alcohol.) Along with many other conservative denominations, the RPCNA interprets the Bible as requiring all elders to be male. Unlike most related denominations, however, deacons in the RPCNA may be either male or female; deaconesses have been permitted since 1888 (with attempts to limit the deaconate to males having failed as recently as 2002). In the late 1930s, the Synod voted to ordain women elders, but the decision was not ratified by a sufficient number of sessions, a process required for all constitutional changes. The sacrament of the Lord's Supper, or Communion, is served to all communicant members present at a church celebrating the sacrament. Until recent decades, only Reformed Presbyterians were permitted to take the sacrament, but members of other denominations considered to be Bible-believing have been extended this privilege in recent decades. However, the RPCNA requires that members of other denominations who take communion be personally interviewed by the session before partaking, which is another practice that distinguishes the RPCNA from other Reformed denominations. The Reformed Presbyterian Church in North America is also a member of the North American Presbyterian and Reformed Council (NAPARC), an organization of confessional Presbyterian and Continental Reformed churches, which also includes the Orthodox Presbyterian Church, thePresbyterian Church in America, the United Reformed Churches in North America, Reformed Church in the United States, and the Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church along with a few other smaller Reformed and Presbyterian denominations as members. |